These Glacier Travel articles are part of the book - Glacier Travel and Crevasse Rescue.

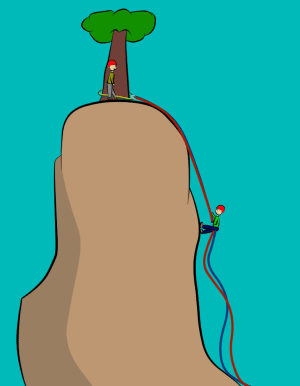

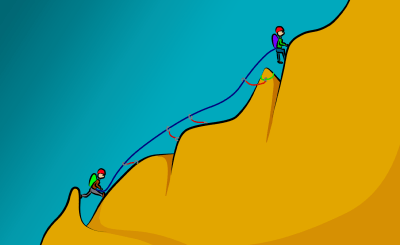

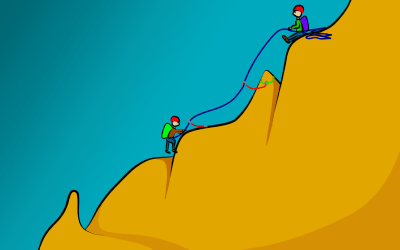

Travelling on a glacier is an exciting element of exploring the high mountains. Many alpine rock climbs can only be accessed by travelling across glaciers, or the glacier itself may be the best route to an alluring summit. Before stepping onto a glacier, it is important to learn how to safely negotiate their hazards.

What is a Glacier?

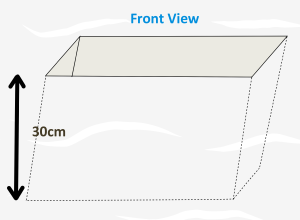

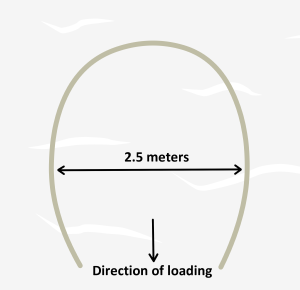

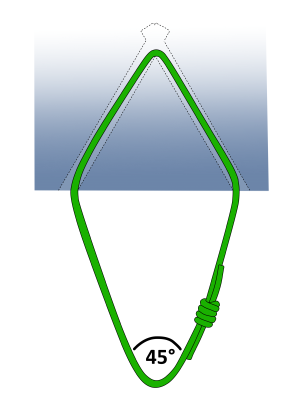

A glacier is a mass of consolidated snow and ice which flows very slowly down a mountain. Different parts of a glacier move at different speeds, similar to the flow rate of water in a river – faster at the center and surface, slower at the sides and bottom where bedrock creates friction. Glacial flow fractures the surface of the ice, creating large cracks (crevasses) which can be up to 45 meters deep, 20 meters wide and hundreds of meters long. Crevasses are the main hazard to people wishing to cross a glacier.

Dry Glaciers

You will encounter dry glaciers in summer, particularly at lower altitudes, when the winter snow has melted and bare ice is exposed.

Because dry glaciers are completely free of snow, it is possible to see all the crevasses and therefore much easier to pick a route to avoid them.

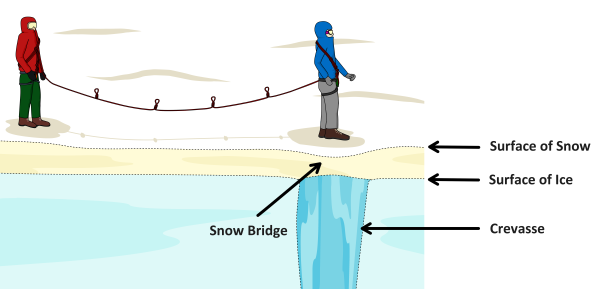

Wet Glaciers

Wet glaciers are snow-covered and much more dangerous. The snow does not fill the crevasses, but instead forms a layer on the surface which hides them.

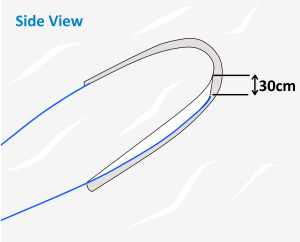

The layer of snow covering a crevasse is known as a snow bridge.

Snow Bridges

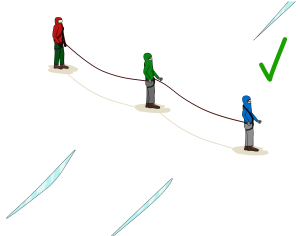

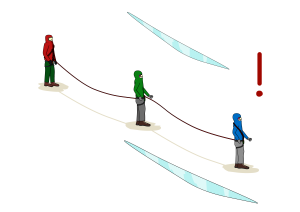

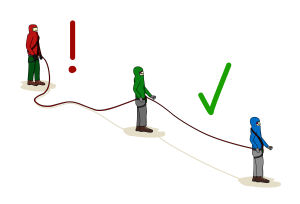

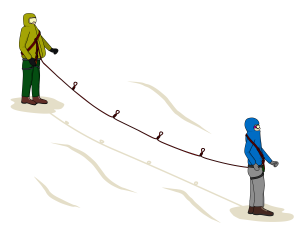

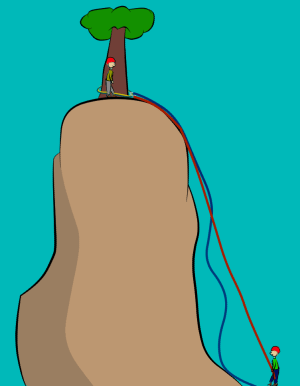

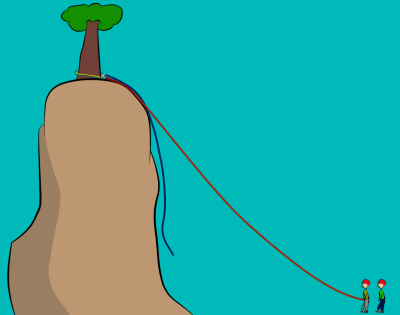

A snow bridge can be thick, well frozen and strong enough to support the weight of a person. Or it could be thin, unfrozen and weak, allowing an unsuspecting climber to fall through into the crevasse beneath. Because of this, it is very important to be roped up as part of a team to help reduce the consequences of falling into a crevasse. Snow bridges are at their strongest early in the morning when the snow is well frozen. Remember this when you’re following your footprints back later in the afternoon.

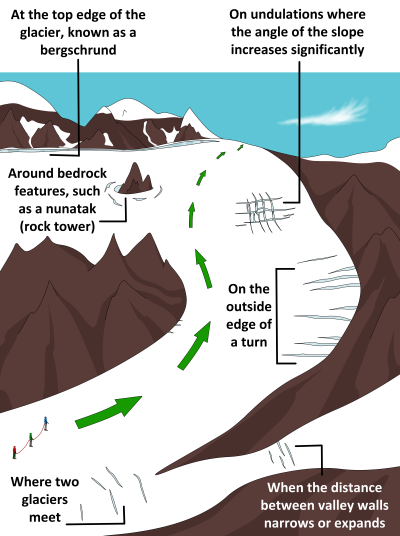

Glacier Travel - Crevasses

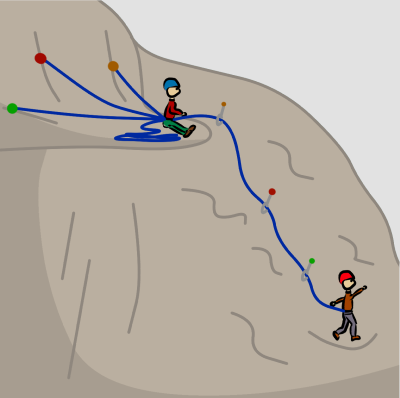

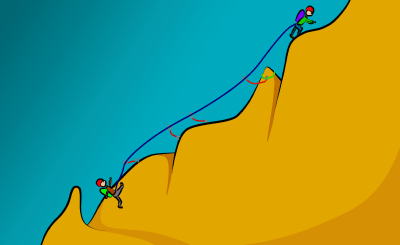

Although crevasses could be almost anywhere and orientated in any direction, there are certain parts of a glacier where they are more commonly found. Crevasses often form in the places shown.

Points of Stress and Compression

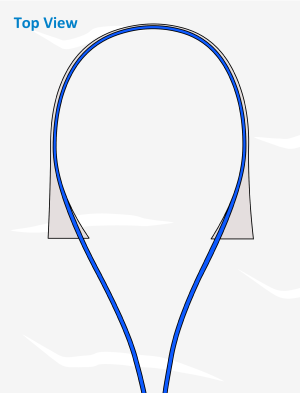

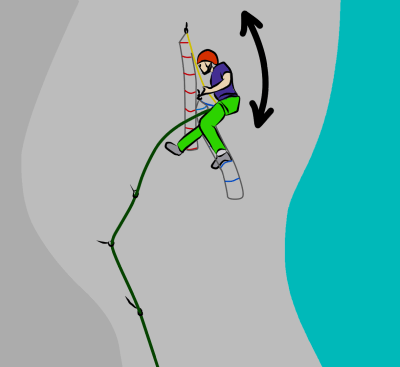

As the ice moves over undulations and around corners, points of stress are created on the outside edge, causing the ice to rip apart and form crevasses. These cracks in the ice typically (but not always) run perpendicular to the flow of the glacier.

Points of compression are created on the inside edges where ice is being pushed together. These areas have the least number of crevasses and usually present the safest route to travel. This is easier to understand if you imagine bending a Mars Bar. Cracks form on the outside of the bend, and chocolate is pushed together on the inside edge.

Finding Crevasses

The first step in choosing a route across a glacier is to figure out where the crevasses are. Here are some tips:

- Study photographs of the glacier before the trip, as some crevasse patterns remain the same year after year.

- On the approach, try to get a good look at the glacier before you reach it. A maze is much easier to negotiate when viewed from outside than from within.

- Look out for sagging trenches on the surface of the snow. Snow covering a large crevasse gradually deforms and sags under its own weight.

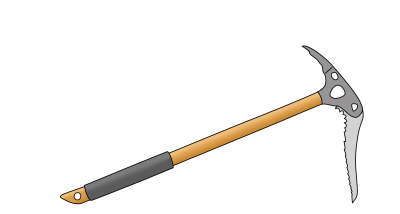

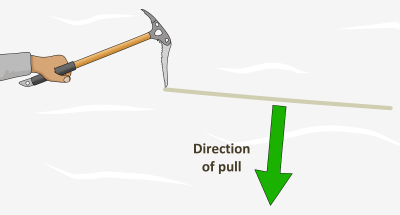

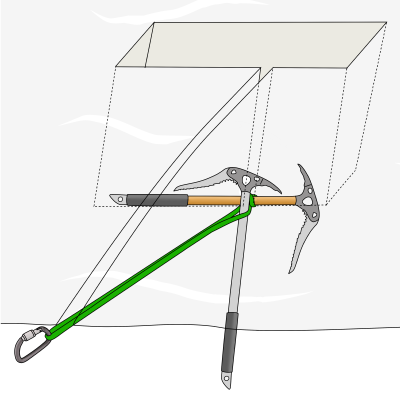

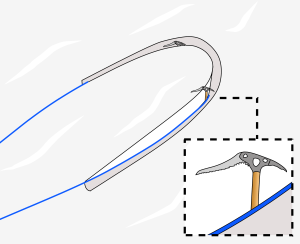

- Probe suspect areas using an axe or ski pole (with the basket removed). Push the shaft of the axe into the snow with a smooth motion. If there is suddenly less resistance, you have most likely found a hole.

- If you find a crevasse, there are probably more nearby.

Other Glacier Hazards

Seracs

A serac is a block or column of glacial ice often formed:

- Where two crevasses intersect

- At the lower end of a glacier

- Where a glacier steepens dramatically

Seracs are dangerous because they can collapse with no warning. If you are below them, you could be hit by ice blocks.

Rockfall

Rockfall is a hazard if travelling on glaciers bordered by steep mountains, or when climbing on rock faces. Rockfall is reduced overnight when the cold temperatures freeze rock in place. The most dangerous times to be exposed to this risk are late morning when direct sunlight melts the bonds between ice and rock, and also in the evenings when meltwater freezes and expands.

Exposure to Seracs and Rockfall

The only way to increase safety when travelling beneath seracs or potential rockfall is to reduce the amount of time you are exposed to the risk. Either alter your route or move efficiently without stopping to minimize the exposure. Factor this in when planning your climb.

Avalanches

Reaching an alpine climbing objective can involve travelling on snow slopes which are prone to avalanches. Avalanche hazard is a complex subject and is not covered in this manual. An excellent resource is Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain by Bruce Tremper.

Whiteouts

When fog or cloud descend on a glacier, snow and sky become one indistinguishable blur of white, with no apparent up or down. Travelling on complicated glaciated terrain in poor visibility can be very serious, as making the correct route choice can be nearly impossible. Even if the weather is clear on the approach, it is worth tracking your route via GPS, so if clouds close in during the day, you will be able to follow your path back.

Assessing Glacier Hazards

With all of these dangers, you may be wondering how anyone has ever survived a glacier crossing! While there are many hazards, there are also many ways of reducing your exposure to them. This mostly boils down to:

- Prior planning (bring the right gear and study maps of your intended route beforehand).

- Waiting for the correct weather and conditions.

- Practising skills (see below)

- Making decisions based on facts, rather than emotions (don’t be afraid of turning back if it’s too dangerous, even if you want to continue).

Training for Glacier Travel

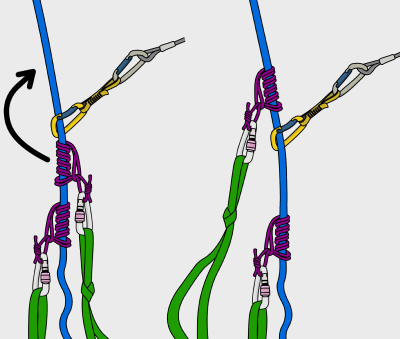

Training for glacier travel means practising the techniques described in these articles. Plenty of practise is essential. Skills such as prusiking out of a crevasse or hauling someone out are strenuous, slow and clunky at first, but with practise you’ll develop a slick and fast technique.

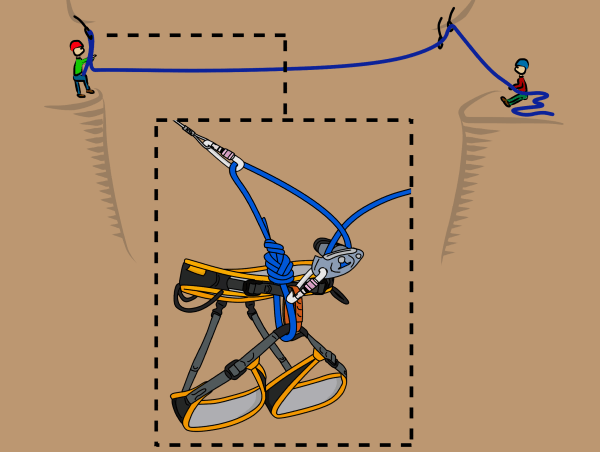

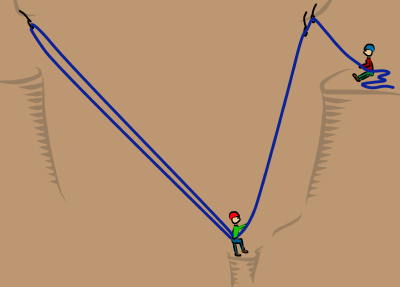

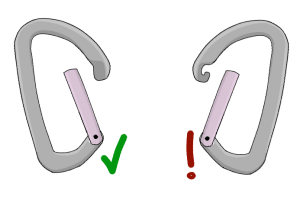

You should aim to reach a level of competence where your snow anchors are always bomber and you can set up any crevasse rescue system quickly and efficiently. Always practise in a group and tell someone at home where you are going.

What To Practise

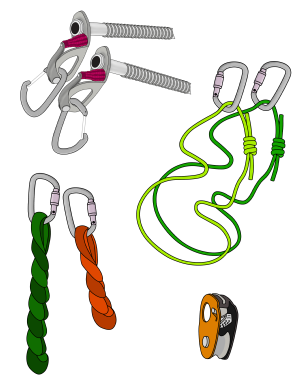

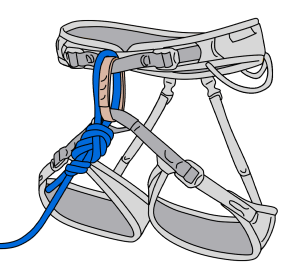

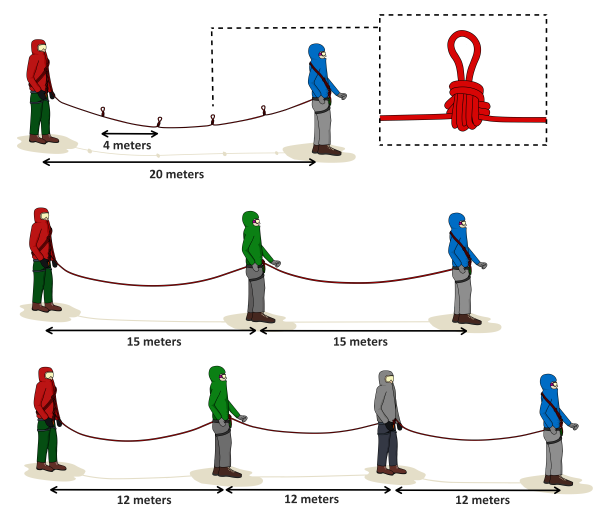

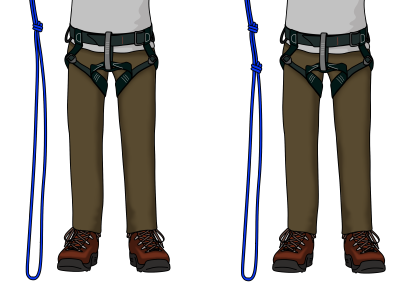

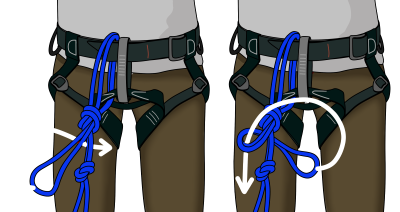

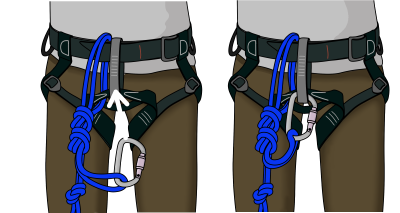

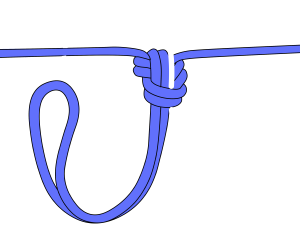

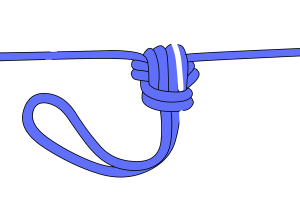

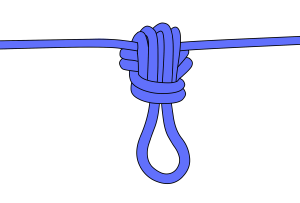

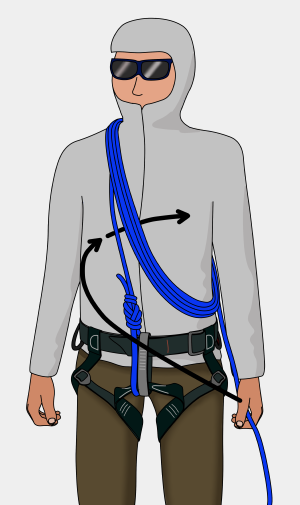

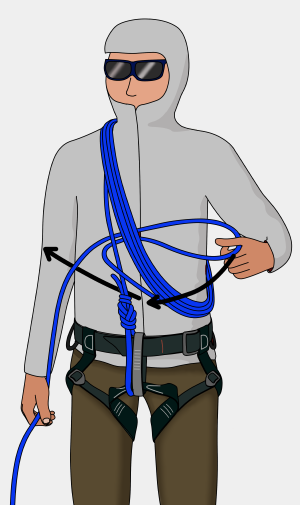

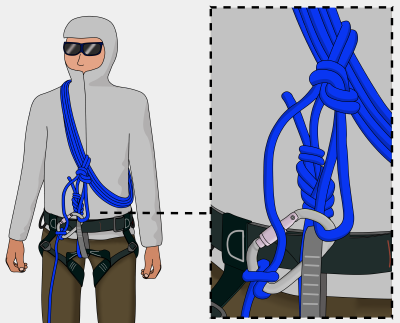

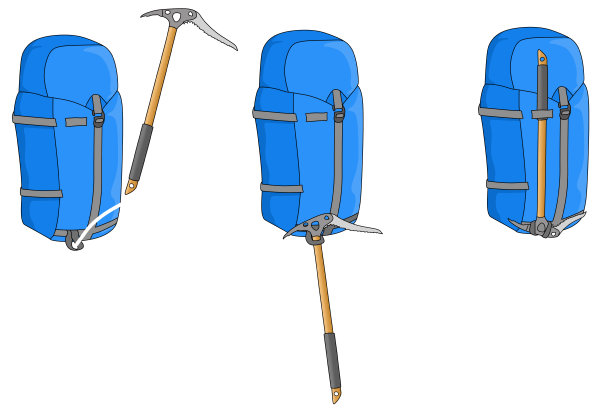

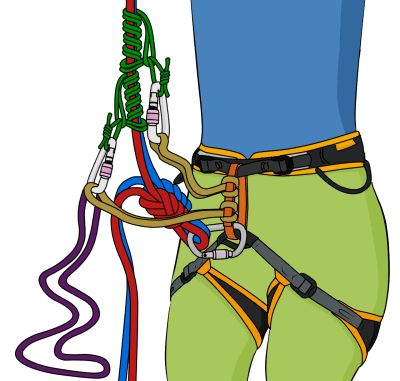

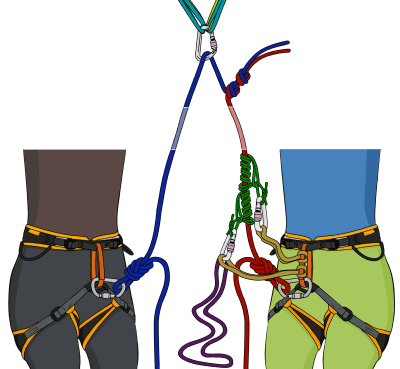

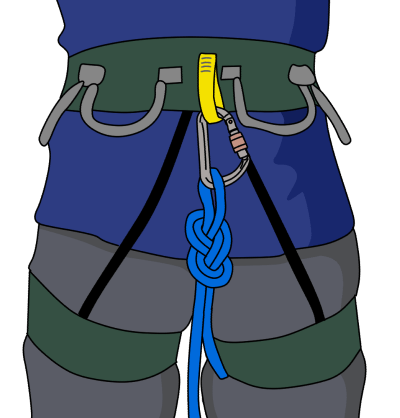

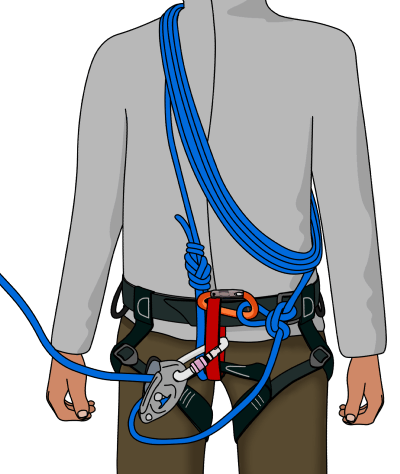

- Tying into the end of the rope and taking coils

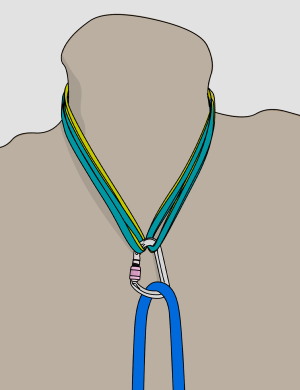

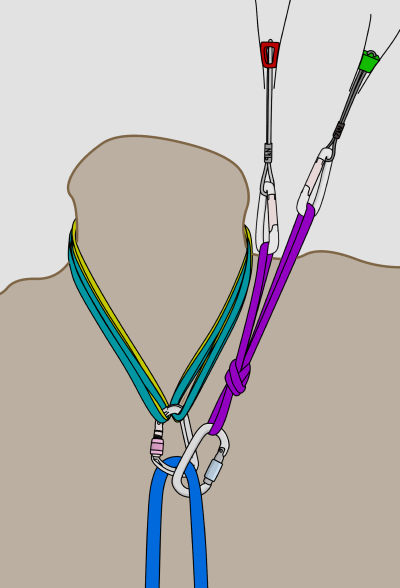

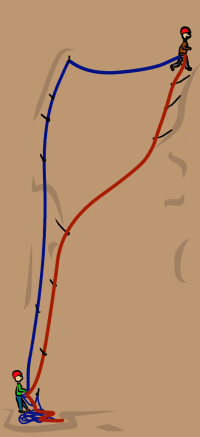

- Tying into the middle of the rope

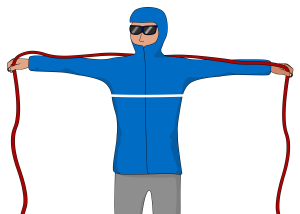

- Measuring the rope accurately with arm spans

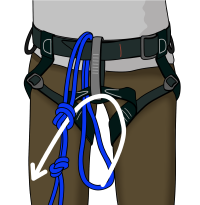

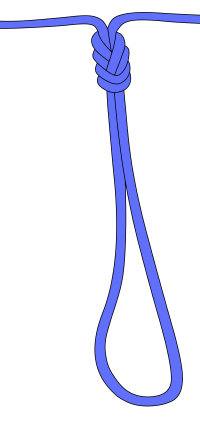

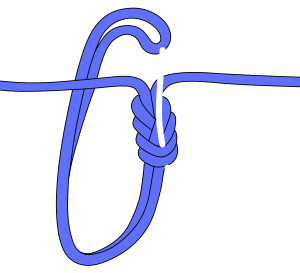

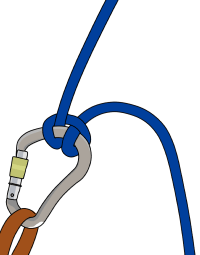

- Tying jamming knots

- Moving on snow of different angles using an ice axe and crampons

- Snow probing

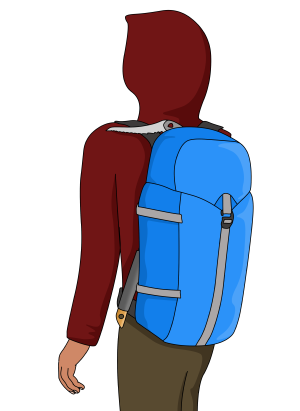

- Wearing the right clothing in different temperatures and conditions

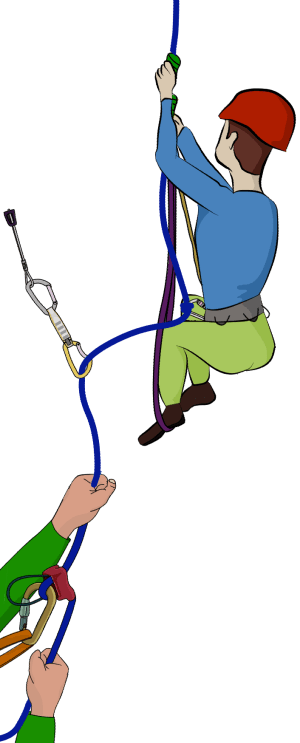

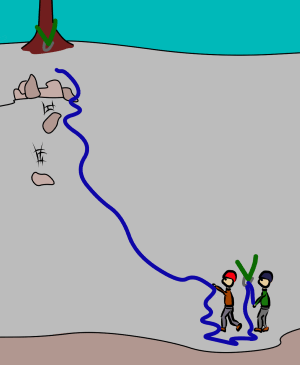

- Moving together with a taut rope

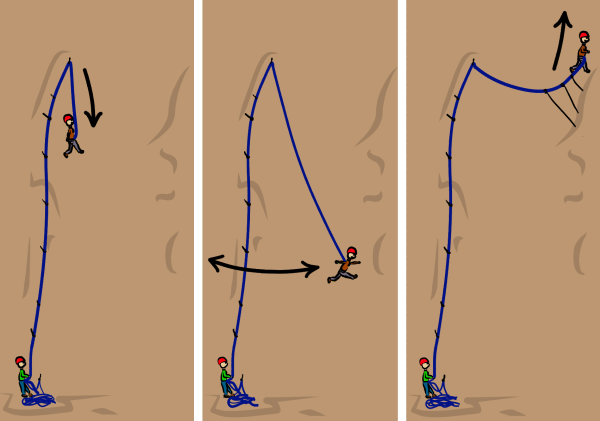

- Various methods of crossing crevasses

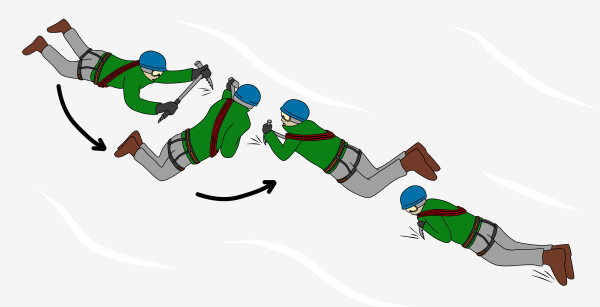

- Self-arresting in different positions

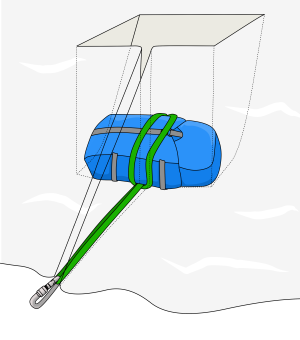

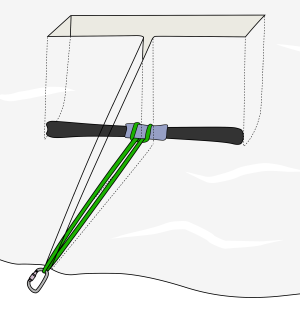

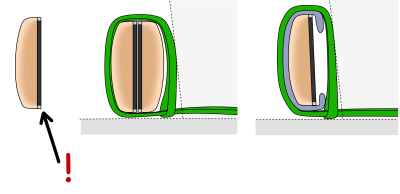

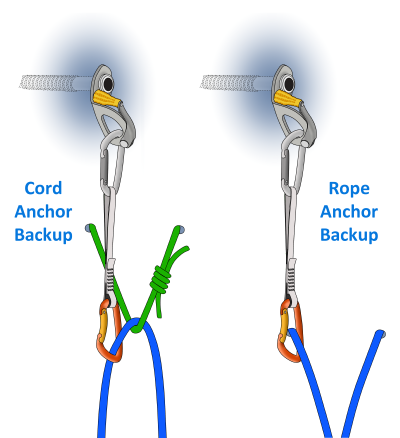

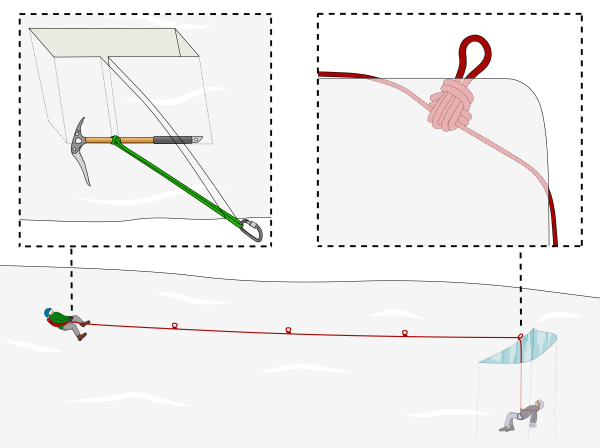

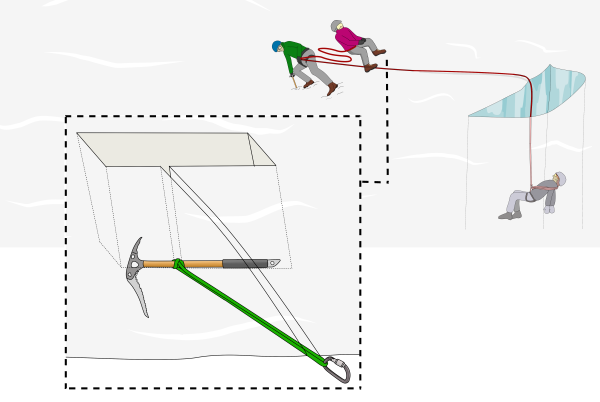

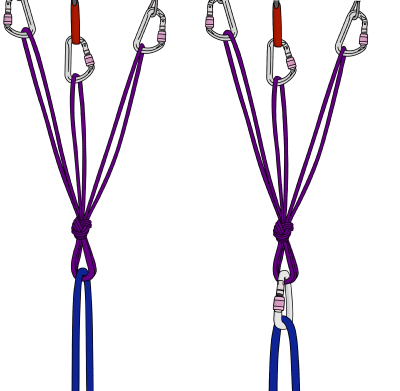

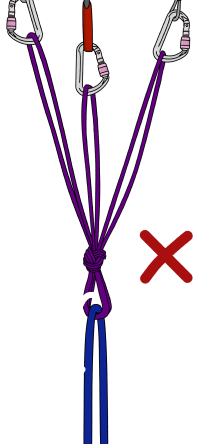

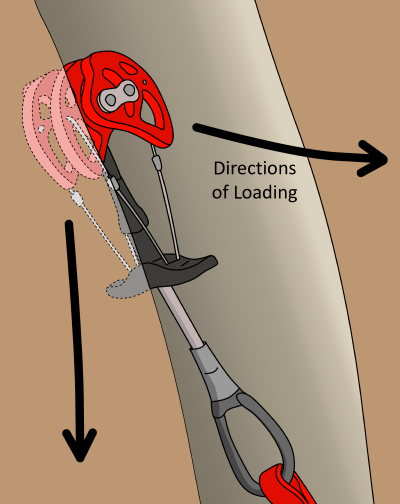

- Making snow and ice anchors in different conditions

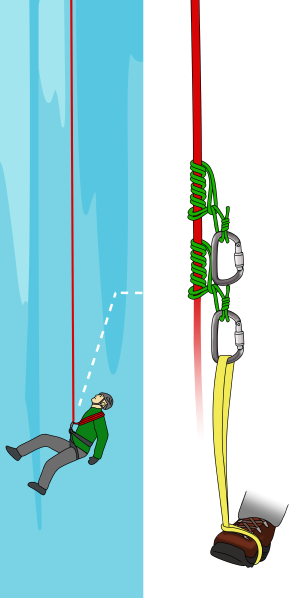

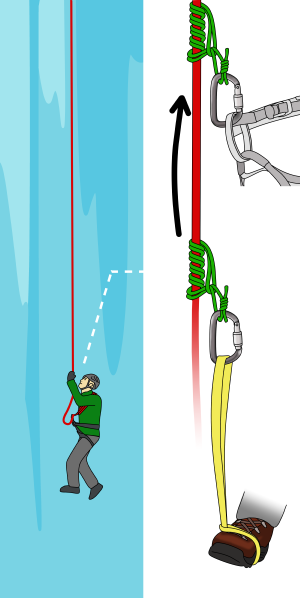

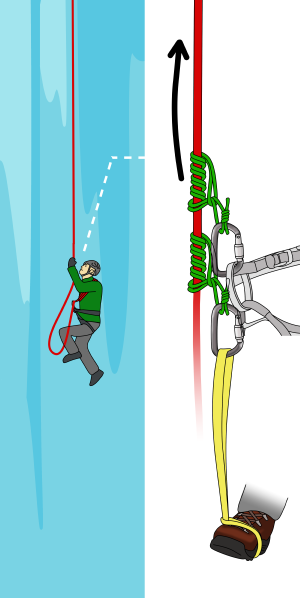

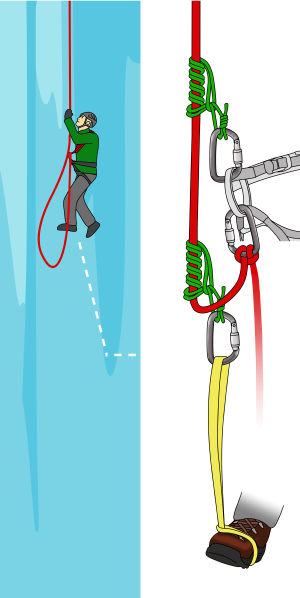

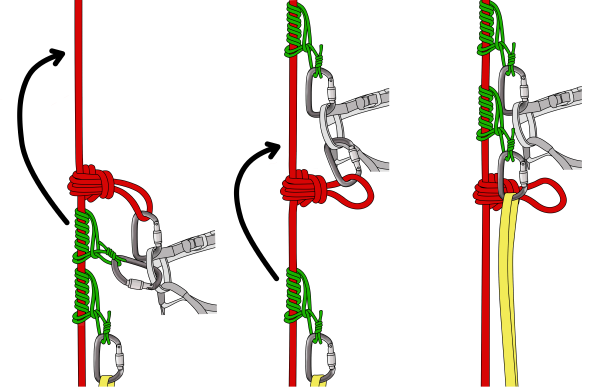

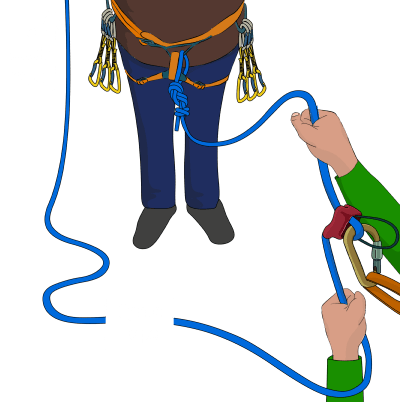

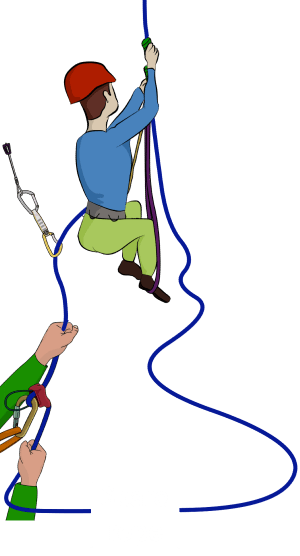

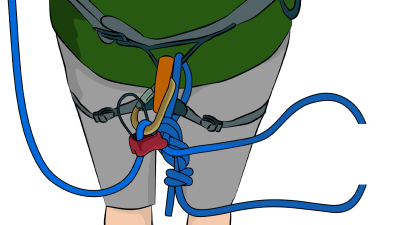

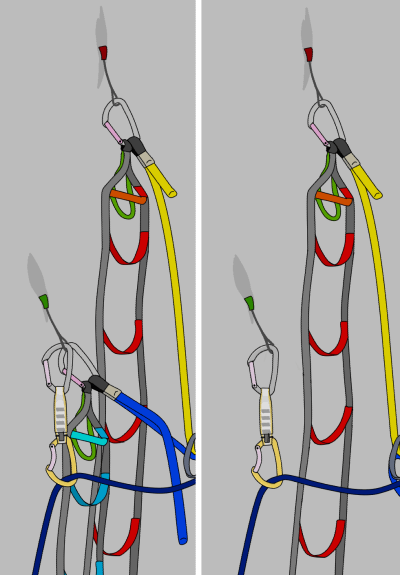

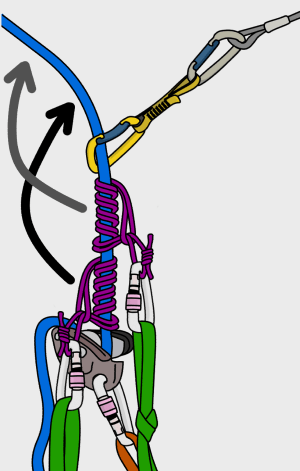

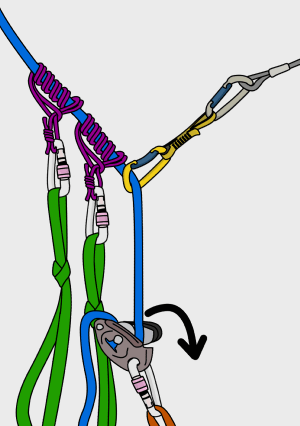

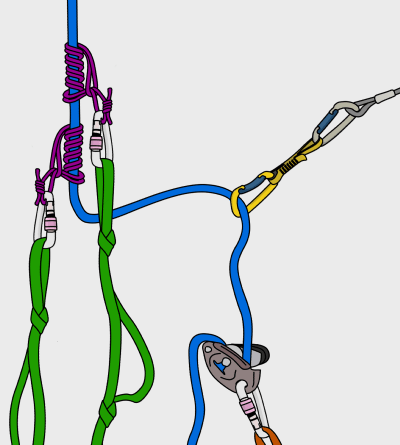

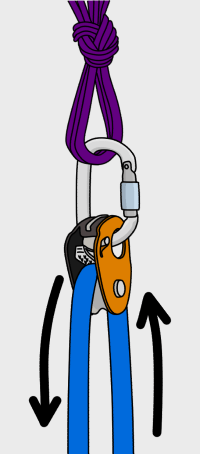

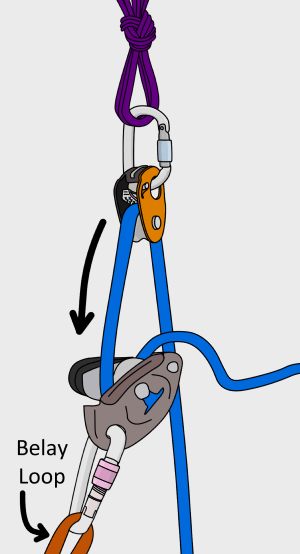

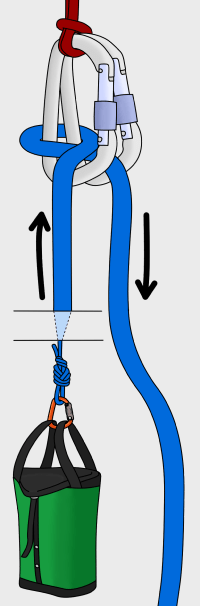

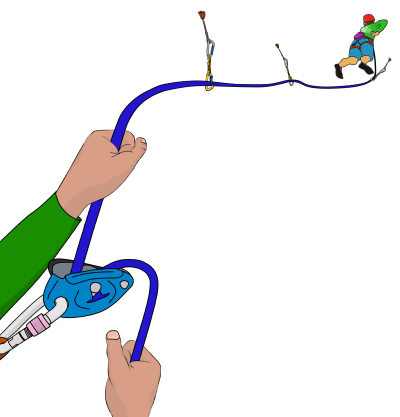

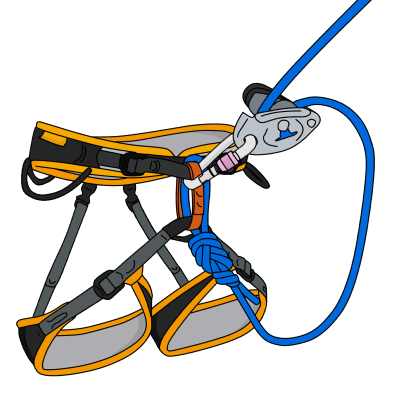

- Prusiking out of a crevasse

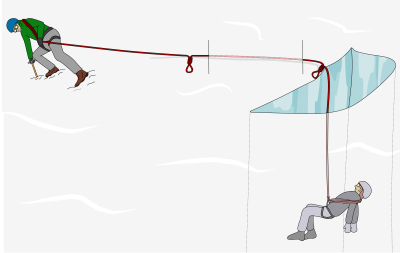

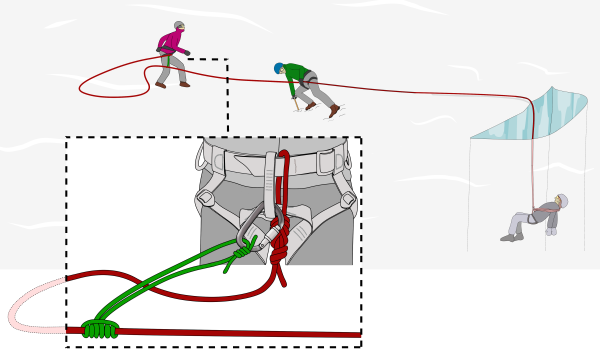

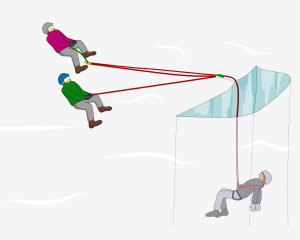

- Hauling a victim out of a crevasse

- Navigating in poor weather

- Map reading and planning a safe route

Where To Practise

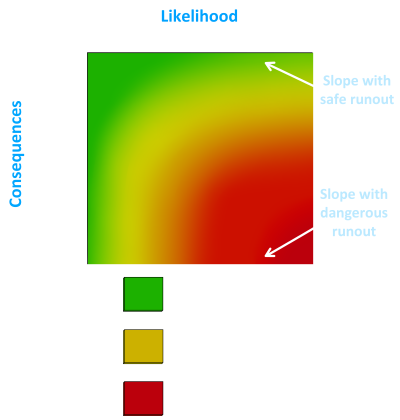

It’s important to build up your experience progressively with regards to terrain. The ideal venue to have your first practise sessions is on a low-angled, non-glacial snow slope which has a safe runout and zero risk of:

- Avalanches

- Crevasses

- Rockfall

- Seracs

Find a safe windscoop to simulate a crevasse, or take some shovels and dig a hole. Once you have built up some skills, progress to a simple glacier which has easy access. Go in a large group for increased safety and fun. With the experience gained from easier terrain, you can then travel onmore complicated glaciers. Only head off on remote, gnarly glacial adventures once you have gained enough real experience.

After each session, review what worked and what didn’t. Focus on improving the things you found most difficult. As with anything worthwhile, it will take time to build up a good level of competence. Trying to shortcut this process is extremely dangerous and will probably result in disaster. Once you have practised and become competent at the skills listed above, you will be ready to do your first real glacier crossing. It is recommended that at least one member of the team has plenty of glacier travel experience, because it takes many glacier crossings to build up skills such as spotting crevasses and other hazards, and negotiating a route through them.